Mojave Max, born in the 90s, crawls into Las Vegas lore

If it’s spring, it’s gotta be Mojave Max time in Southern Nevada.

Many area residents know Mojave Max from his annual emergence contest, where elementary school students participate in the Punxsutawney Phil-esque tradition of guessing when the desert tortoise will emerge from his burrow after brumation (hibernation for reptiles).

But some may not know where Max came from or who created him.

The Clark County Desert Conservation Program’s mascot was born from an educational campaign aiming to help the desert’s youngest inhabitants learn to enjoy the outdoors responsibly. The slogan: “Respect, protect and enjoy.”

Mojave Max came from the mind of Shauna Walch, who worked for advertising agency Dunn Reber Glenn Mars. She was tasked with helping create content for the CCDCP’s early public service announcements in 1991.

Walch wrote and read radio scripts for the program’s PSAs that took inspiration from stand-up segments from “Seinfeld,” with jokes read in a wacky voice about how humans weren’t the desert’s first inhabitants. But the PSAs didn’t go over as planned.

“It just fell flat, and that’s one of those (moments where) you’re just like, ‘Oh no. Now I have to go back to the drawing board again,’ and I was used to that in advertising,” Walch said.

She scrapped the “Seinfeld”-style stand-up and started thinking about her life growing up in Las Vegas, along with the desert tortoise’s recent classification as a threatened species in 1990.

“We were outdoors from the time we were little kids.” she said. “I really started to think about my own experience, and that real living desert experience, and I thought, it needs to be the desert tortoise to be a spokesperson, not just for himself, but for the entire desert.”

She started writing stand-ups with the tortoise character in mind, but still didn’t have a name. After agreeing to stick with a tortoise mascot, CCDCP decided that Clark County School District students should name the character.

Walch said some pitched names were Sargent Shell, LaShelda, Hardback and — most fitting for the early 1990s — Snoop Tortie Tort.

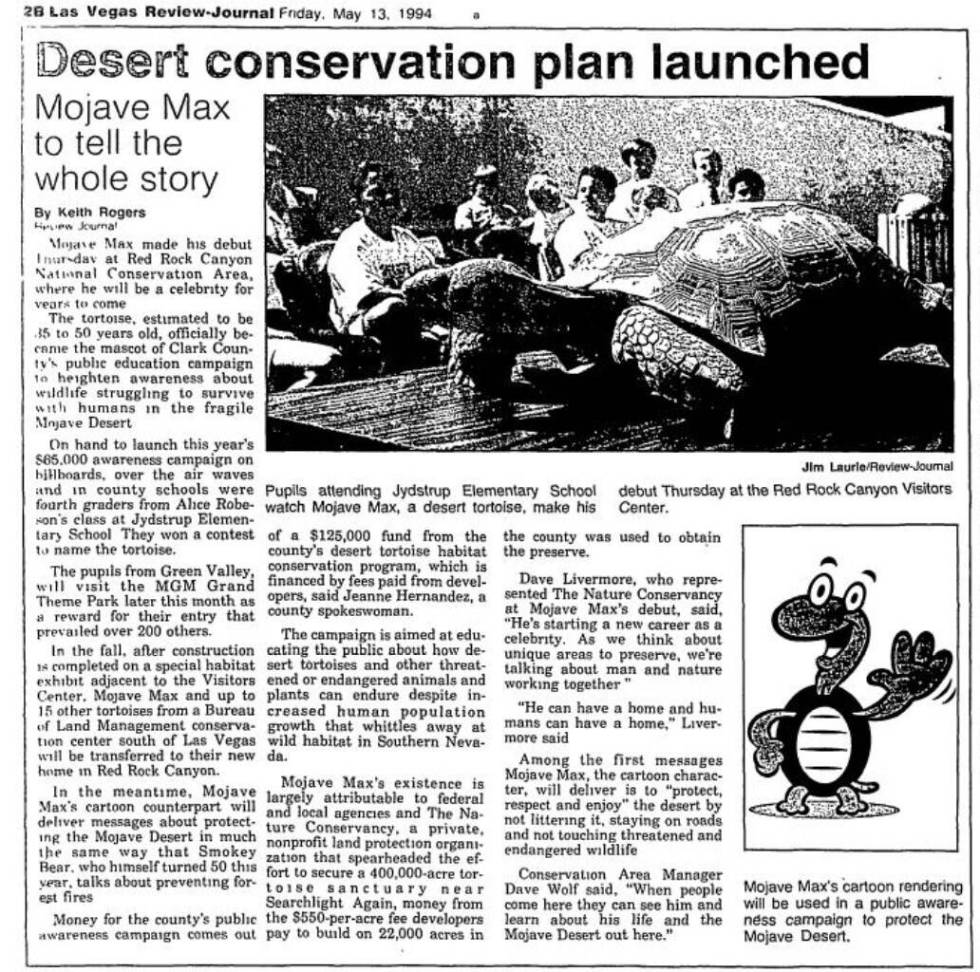

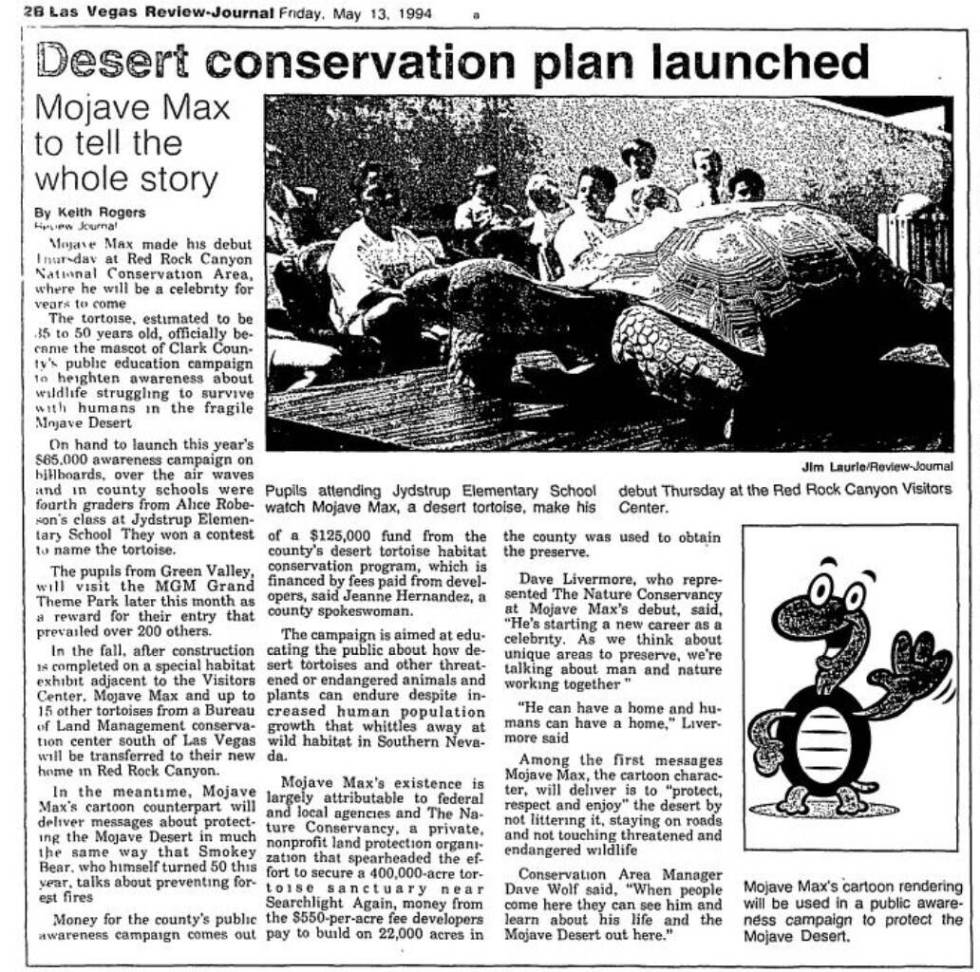

But it was a fourth-grade class at Jydstrup Elementary School that gave Max his name in 1994. The tortoise became part of the county’s $65,000 public education campaign about the fragility of the Mojave Desert, former Review-Journal reporter Keith Rogers reported at the time.

The students took a field trip to Red Rock Canyon Visitors Center, where the first two Max tortoises lived before 2017.

The emergence contest wasn’t a part of the program’s original campaign, said Audrie Locke, public outreach coordinator for CCDCP.

The first contest, sponsored by KNPR, was organized by community members who felt that Mojave Max needed an ongoing connection to students, Locke said. It received over 10,000 guesses from district students, according to RJ archives.

That initial success grew into an annual event.

“It was made obvious to us that this is something that we should do regularly, so we went ahead and took it on,” Locke said.

The student who wins the emergence contest receives a class field trip to Max’s habitat at the Springs Preserve, along with other prizes.

The suited mascot version of Max, created in 2000 to go along with the real-life Mojave Max, helped the tortoise explode in popularity with kids and parents.

“When we have the costumed mascot out and in events, the adults get just as excited and want to take just as many pictures as the kids,” she said. “He’s very recognizable, and that’s obviously what you would want from any type of mascot — for people to have a warm feeling about it.”

The Max campaign also sparks learning for families about desert conservation.

“Many times children will teach their parents. … So, we really feel that starting at the elementary school level is not just educating the elementary school kids, it’s educating the family as a whole,” she said.

Pandemic struggles

The program faced an unprecedented challenge when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, said Shelly Kopinski, director of programs for the nonprofit Get Outdoors Nevada.

The nonprofit, which administers Mojave Max programming in schools, struggled to promote the message. Classroom discussions and assemblies were out, and online was in.

“It’s harder to get questions and feedback from the kids and really engage with them one-on-one when we’re over Zoom or Google Meet,” Kopinski said. “We’re just so excited this year is our first year back full 100% in the classroom. We’ve loved every minute of it.”

She’s noticed greater student engagement, especially with the desert animal specimens the program brings into schools to teach students about wildlife.

“It’s one thing to be able to look at something on a screen, but it’s quite another if they get to see it close up or get to touch and feel it. It’s a completely different experience,” she said.

Still, technology remains a large part of programming. Students now watch videos in the classroom and on social media, including a music video, to learn about conservation, desert tortoises and more.

Locke said a plan is being created to expand the campaign to middle and high school students that includes high school student ambassadors going to middle schools to talk about desert conservation.

“(We want to) encourage kids to consider biology or the sciences as a career, ” Locke said. The programming is planned to roll out by the end of summer.

Walch said she feels proud to have contributed to the Mojave Max program.

“I always tell people that Mojave Max was my first child that I helped birth, and I certainly didn’t raise him,” she said. “He was raised by a much larger community of people who got involved.”

Contact Taylor Lane at tlane@reviewjournal.com. Follow @tmflane on Twitter.

Article written by Taylor Lane #ReviewJournal